To prev. page

The Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies of the Bank of Japan (BOJ-IMES) and the Bank of Korea Economic Research Institute (BOK-ERI) held a joint workshop at the main building of the BOK in Seoul on December 21, 2023. This workshop was initiated in 2017 and has been held six times in the past. The theme of this seventh workshop was “Growth and Inflation in an Aging Economy.” Asenior economist from the Bank for International Settlements Representative Office for Asia and the Pacific in Hong Kong (BIS-HK) also participated.

In the morning sessions, Chief Economist and Deputy Governor Jae Won Lee of the BOK gave a welcome speech, and then, Director-General Taehyoung Cho of BOK-ERI and Executive Director Masaaki Kaizuka of the BOJ delivered their presentations about the Korean and Japanese economies. In the afternoon sessions, five papers (2 papers by BOK-ERI, 2 papers by BOJ-IMES, and one paper by BIS-HK) were presented. This newsletter provides an overview of the paper presentation sessions.

1. Studies on Determinants of Fertility Rate

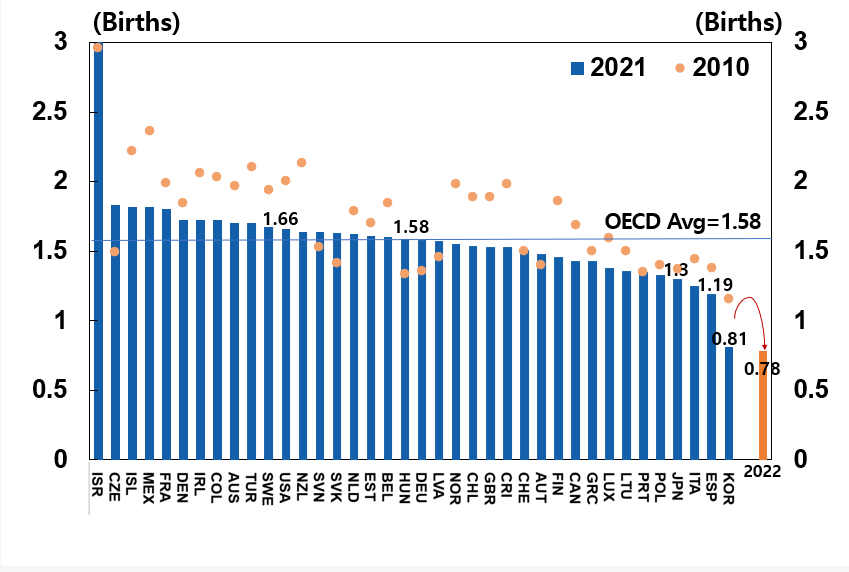

The population has been aging worldwide, especially in developed countries, due to a decline in birthrates and increased longevity. The average fertility rate among OECD countries has declined over the past 60 years (from 3.29 in 1960 to 1.58 in 2021). In particular, the total fertility rate of South Korea was 0.81 in 2021, significantly lower than unity and lower than any other OECD country, including Japan (1.30 in 2021). In Korea, therefore, there are increasing concerns about the economic impact of the sharp decline in the fertility rate, and how to contain the decline is considered an urgent policy agenda. Against this backdrop, Dr. Won Sung presented his empirical study analyzing the determinants of birthrates, using data on total fertility rates in OECD countries.

(Figure 1) Total Fertility Rates in OECD Countries

According to previous studies, in addition to economic factors, ‘social and cultural factors’ and ‘policy and institutional factors’ can reduce the birthrate. This study explores the factors underlying a decline in fertility by examining a wide range of different factors, including their proxies. It conducts a panel data estimation using as the dependent variables the total fertility rates of 35 OECD countries for which the necessary data are available. The explanatory variables include the following: economic growth rate, youth employment rate, and real housing prices as economic factors; urban population density (population density times urban population ratio), share of births outside of marriage, and female employment rate as social and cultural factors; and indicators of public expenditure related to household benefits and allowances, use of childcare leave, etc. as policy and institutional factors.

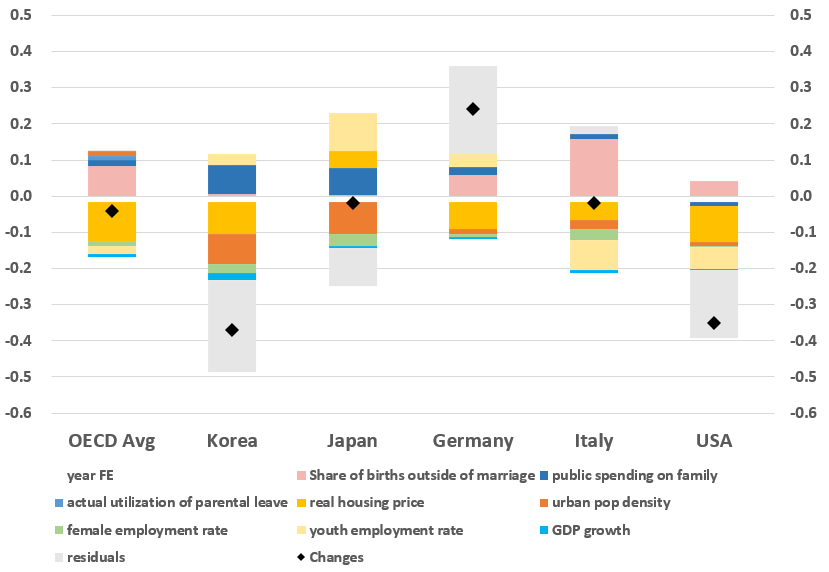

The results show that the youth employment rate has a statistically significant (positive) effect and real housing prices has a statistically significant (negative) effect on the fertility rate. They also show that urban population density affects the fertility rate significantly negatively and that the share of births outside of marriage affects it significantly positively, while the shares of births outside of marriage are extremely low in Japan and South Korea (around 2%) compared with the average of OECD countries (43%). In addition, the effect of ‘policy and institutional factors’ is positive and statistically significant for the fertility rate, implying that fertility rates tend to be higher in countries with more generous household benefits and allowances and with more active use of parental leave. A factor decomposition based on the estimates shows that, high real housing prices and high urban population density made a negative and sizable contribution to the fertility rate in South Korea between 2002 and 2021 (Figure 2).

(Figure 2) Decomposition of Changes in Total Fertility Rates between 2002 and 2021

Based on this result, Dr. Sung pointed out the possibility that the concentration of population in urban areas has caused the fertility rate to decline because soaring real housing prices and excessive competition for education and employment have made the cost of living and having children much higher. He also reported that if there were improvements in factors other than ‘social and cultural factors’ to the average level of the OECD countries, South Korea's fertility rate would increase by about 0.27 child per woman, exceeding one.

Next, Dr. In Do Hwang, pointing out that the falling marriage rate has contributed to the decline in the fertility rate in South Korea, presented his latest paper (co-authored with Dr. Yunmi Nam, Ref. (1)), which explores the factors that have affected South Korean decision-making regarding marriage and fertility. His study is based on the results of a unique online survey consisting of questions about marriage and fertility, which included 2,000 Korean men and women aged 25-39 (1,000 unmarried and 1,000 married with no children).

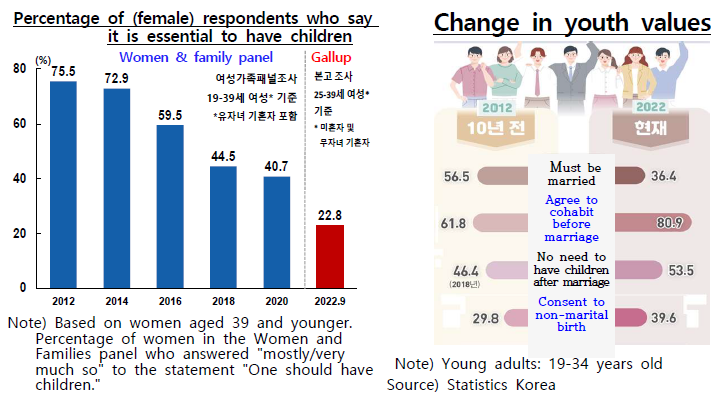

More than one-third of the unmarried respondents answered that they wanted to get married, but their current situation was not conducive to doing so (due to issues related to housing, employment, and others), while more than a quarter of the respondents answered that they did not want to get married (and would prefer to remain single). In addition, more than 40% of the respondents said "I cannot afford to pay for childcare and education" as a reason for not having children, based on their own or their neighbors’ experience. About 20% said "I think childless life is more comfortable." Along these lines, other South Korean public opinion surveys indicate that young people's values and attitudes toward marriage and childbirth have changed significantly over the past decade, as evidenced by the decline in the number of people who believe that they should get married and have children (Figure 3).

(Figure 3) Results of Other Surveys of Attitudes to Marriage and Childbirth in Korea

This survey was devised in such a way as to facilitate identification of the causes of the respondents’ answers and their significance. Respondents were randomly divided into four groups: (i) three treatment groups, consisting of those who were given information and questions about factors that might affect marriage and childbirth/childcare before being asked questions, and (ii) one control group consisting of those who were not. Then, all the groups of respondents were asked the following same questions: "Do you want to get married?" and "Do you want to have (how many) children?" The comparison is made for the results for these different groups, namely, treatment groups who were given one of the following three types of information, (1) information on housing costs, (2) information on childcare costs, and (3) information on medical costs, and (4) the control group with no information on any of these factors. This comparison makes it possible to assess the relative importance of each of factors (1) to (3) in the decision to marry and have children.

The study then estimates the effects of these factors on the respondents’ answers to the questions (e.g., desire to marry <Yes or No>) in a probit model, controlling for the groups each respondent belongs to and for the respondents' attributes (gender, age, education, income, etc.). The results show that, the treatment effect of (1) housing costs is significantly negative and particularly pronounced for the respondents living in urban areas, while the treatment effects of (2) childcare costs and (3) medical expenses are not statistically significant. The results suggest that the housing cost burden has a negative effect on marriage intention and the desired number of children. In a separate analysis, the study shows that there are clear differences in willingness to marry among respondents between those who have regular jobs and those who do not, as well as between those who are temporarily employed and those who are employed in the public sector, suggesting the importance of employment security in marriage decisions.

With declining birthrates and population aging in developed countries, including Japan, it is important to investigate the economic impact of these trends. It is also important to investigate empirically and experimentally the background and factors surrounding the declining birthrate and the falling marriage rate, as in this analysis.

2. A Study on the Impact of Changes in Population Growth on TFP Growth

Dr. Hiroshi Inokuma (BOJ-IMES) presented his theoretical study (co-authored with Dr. Juan M. Sánchez of St. Louis Fed), which incorporates an endogenous growth mechanism into firm dynamics and analyzes the impact of changes in population growth rate on TFP (total factor productivity) growth rate through firms’ economic activities.

Previous studies have shown, both theoretically and empirically, that a decline in the population growth rate reduces the birth of new firms (i.e., firms' entry into the market) and decreases the market share of relatively young firms. On the other hand, the actual data from Japan and the U.S. show that young firms have higher productivity growth rates than older firms. These findings suggest that a lower population growth rate may reduce the economy-wide TFP growth rate through a decline in the market share of young firms.

In their model, entrepreneurs are assumed to enter the market if the expected return on their new business is positive. The population growth rate, which boosts aggregate demand, is therefore positively correlated with the rate of business entry. As is in the standard framework of endogenous growth theory, it is also assumed that new businesses increase their own productivity to a level higher than the average productivity of the market. The more new businesses enter the economy, the higher the average productivity of the market as a whole, and the greater the economy grows. Whether or not a firm can achieve its productivity target and whether or not it is forced to exit the market are determined stochastically. In this setting, changes in the population growth rate determine changes in the productivity of the economy. The model reproduces the key firms’ characteristics, which are important for studying firm dynamics, in data such as the average number of employees (level and growth rate) and the age profile of the business closure rate.

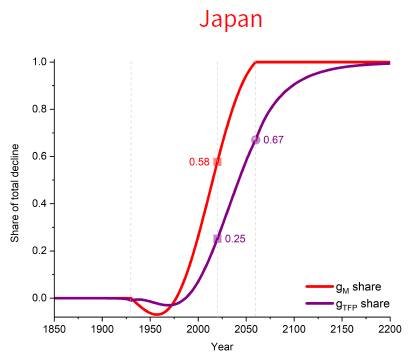

Japan's labor force growth rate is projected to decline by about -2.4 percentage points annually, from about +1.0% in 1920 to -1.4% in 2060. Based on the model, this results in a decrease in TFP growth of about -0.42 percentage points annually in the long run. However, only about 25% of its impact (downward contribution) on the TFP growth rate had materialized (blue line in Chart 4) in 2019, when the working population growth rate was about -0.4% (about 58% of the total decline of -2.4 percentage points) (red line in Chart 4). Even around 2060, when the decline in the working population growth rate is fully realized, its materialized impact (downward contribution) will be only around 67% of the entire impact. The model’s prediction suggests that the impact of the decline in the working population growth rate on the TFP growth rate materializes sluggishly over a very long period of time.

(Figure 4) Realized Ratio of Decline in TFP Growth Rate due to Decline in Labor Force Growth Rate

In many economic theories, productivity is given exogenously. However, it is believed in practice that a country's productivity is endogenously affected over a long period of time by trending changes in its social and economic structure, such as demographic changes. Theoretical consideration along these lines is important for quantitatively assessing these (super-) long-run effects.

3. A Study on Term Structure of Inflation Forecasts Disagreement and Effectiveness of Monetary Policy

Dr. Dora Xia (BIS-HK) presented her paper (co-authored with Mr. Alessandro Barbera and Dr. Sonya Zhu, Ref. (2)), which analyzes empirically how the term structure of inflation forecasts disagreement and monetary policy transmission are related, using the decomposition of the inflation forecasts disagreement into long-term and short-term components.

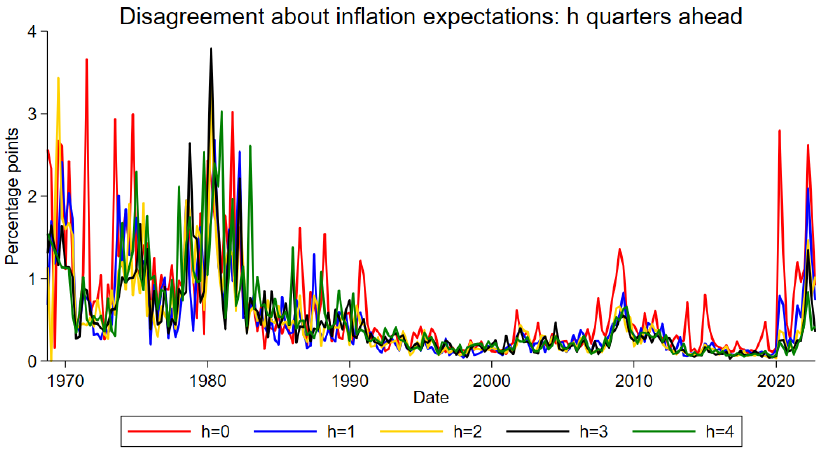

Inflation expectations have been one of the key factors that influence households’ and firms’ economic activities and stabilizing them is important for macroeconomic stability as a whole. Central banks have been monitoring inflation expectations using a variety of indicators and constantly making efforts to determine whether they have been anchored around the central banks’ inflation targets. It is also well known, however, that there are dispersions in inflation expectations depending on forecasters, and that the forecasts disagreement varies over time and across forecasting horizons, reflecting diverse views of the forecasters on short-, medium-, and long-term inflation developments (Figure 5).

(Figure 5) Time-Variations and Dispersions in Inflation Expectations for h Quarters Ahead

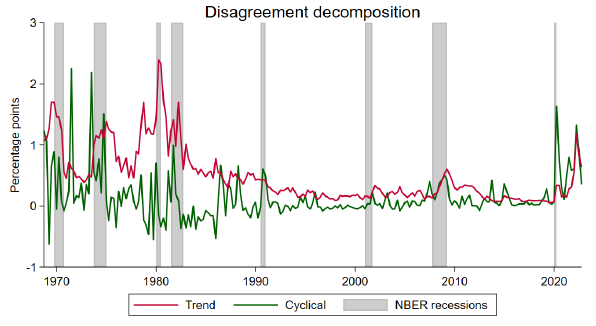

This study first measures the dispersions of the expected inflation rates as the statistical variance of forecasts among respondents of the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF), which asks professionals about their forecasts of the U.S. inflation rate. It then decomposes the dispersions into the two components: (1) a "trend component" that follows a random walk and has an impact on the level of the inflation rate over the long term, and (2) a "cyclical component" that follows an AR(1) process and mainly determines the slope (short-run fluctuations) of the inflation rate. The trend component fluctuated substantially during the period of high inflation in the 1970s, declined in the 1980s when Paul Volcker was the Fed chairman, and then generally remained low during the "Great Moderation" period in the 2000s (Figure 6). During the recovery phase following the COVID-19 pandemic, not only the cyclical component but also the trend component has seen an increase in dispersions in the direction of high inflation.

(Figure 6) Time-Variations in Trend and Cyclical Inflation Forecasts Disagreement

The study also estimates how the transmission and impact of monetary policy shocks on the inflation rate change with the size of inflation forecasts disagreement. The results show that trend inflation disagreement does not significantly affect the transmission of monetary policy shocks on the inflation rate, while high disagreement on cyclical inflation has effects undermining monetary policy transmission. That is, with higher cyclical inflation disagreements, a monetary tightening shock (an unanticipated interest rate hike) can push up the inflation rate (both expected and realized) in the short run. Regarding this point, Dr. Xia pointed out that the Fed's monetary tightening may be perceived by market participants as a kind of positive news (signal) regarding the U.S. economy in the near term. These results suggest that central banks' proactive communication with the market could enhance the effectiveness of monetary policy by reducing dispersions of inflation expectations, in particular those of cyclical components.

References

Click on the number at the end of each item to return to the main text.

- Nam, Yunmi, and Hwang, In Do, “Economic and Non-economic Determinants of the Lowest-Low Fertility Rate in Korea: An Analysis of Survey Experiments,” Bank of Korea Working Paper 2023-24, 2023 (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4655594). (1)

- Barbera, Alessandro, Dora Xia, and Sonya Zhu, “The Term Structure of Inflation Forecasts Disagreement and Monetary Policy Transmission,” BIS Working Papers No. 1114, 2023 (available at https://www.bis.org/publ/work1114.htm) (2)