BOJ-IMES special trialogue

Research at Central Banks

Series 1: Interactions between Central Banks and the Academic Community

Series 1: Interactions between Central Banks and the Academic Community

-

Series 2: "Art versus Science" in the Conduct of Monetary Policy

-

Series 3: The Role of Central Bank Research for Communication

- To "Research at Central Banks" Top Page

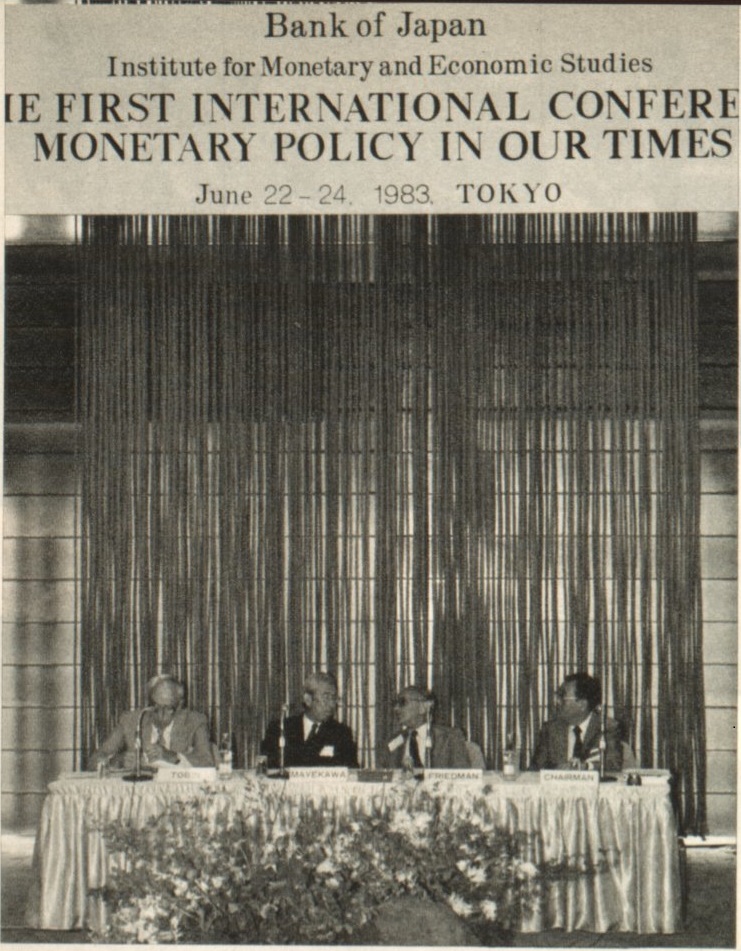

October 2022 marked the 40th anniversary of the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies (IMES) of the Bank of Japan (BOJ).

Established by the BOJ 40 years ago, the IMES promotes fundamental research on theoretical, institutional and historical matters of monetary economy. The IMES also has a mission to promote domestic and international interactions with researchers in academia.

To celebrate this anniversary, the IMES held a special trialogue event between the two Honorary Advisers to the IMES, Professor Carl E. Walsh (University of California, Santa Cruz) and Professor Athanasios Orphanides (MIT Sloan School of Management), and Masazumi Wakatabe (Deputy Governor of the BOJ) under the title of Research at Central Banks.

They had lively discussions on the history of interactions between academics and central bank economists, on the "Art and Science" of monetary policy, and on the role of research for communication purposes. The transcript of the discussions is presented here in a series of three consecutive newsletters.

How have the interactions between academia and central banks evolved?

Wakatabe (Deputy Governor of the BOJ) I am happy to welcome our two distinguished Honorary Advisers to the IMES. The importance of the interaction between the academic and the policy research communities is the very reason we have the Honorary Advisers to the IMES. As a historian of economic thought, I would first like to ask both of you about how the relationship between academia and central banks has changed over time.

Distinguished Professor Emeritus

University of California, Santa Cruz

Walsh (University of California, Santa Cruz) The interactions have evolved dramatically since I was in graduate school back in the early 1970s. When I was a Ph.D. student, Robert Lucas published his famous article on the neutrality of money and the academic community followed his work.[1]

In his framework, monetary policy issues, such as helping stabilize the real economy or controlling inflation, were not interesting research topics for academic economists, because only surprises mattered for the effect of policy; the design of policy rules was irrelevant. So, the academic work was not really posed to address the issues that central bankers were concerned with.

This situation gradually changed during the 1980s to 1990s as nominal rigidities were integrated into the macroeconomic model that become what we now call the New Keynesian model.

Importantly, expectations matter in the New Keynesian model, and thus the way the central bank behaves systematically is important for influencing the real economy and inflation. In this new framework, questions like "What is an optimal policy rule?" became interesting not just for central bankers, but also for academics.

In this way, the New Keynesian framework opened up a huge common ground for academic and policy researchers, where academics could contribute to issues that the policymakers were interested in. Conversely the questions central bank economists were struggling with became ones that academic economists were also interested in focusing on.

I think the interaction between academics and central bank research community over the last 30 years has been quite productive. For example, many central bank researchers including Athanasios [Orphanides] have published in top academic journals and have had a huge influence on the academic community.

Orphanides (MIT Sloan School of Management) That's very nice, Carl [Walsh]. Let me start by saying that the most important thing to recognize for policy purposes at central banks or in other policy institutions more broadly is that all policy is really made in an environment of uncertainty. This is because the economy changes over time and so does our understanding of it.

And in such an environment, research is absolutely essential. Research teaches us what we are more uncertain and more certain about.

In particular, research is essential for understanding what has gone wrong in the past. Sometimes it takes decades to understand why some major economic disasters happened and research is what guides us to improve policy.

Let me give you an example based on my study on the history of the Federal Reserve: The Great Depression. In the 1960s, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz published the magnificent volume on the Great Depression that completely changed our thinking about what had happened. [2]

The point here is that it took another 20 years before it was recognized in the profession as the best explanation and understanding of what had gone wrong with Federal Reserve policy during the Great Depression.

And it took a few more decades for the Fed to finally come to terms with it. This was in a speech by Ben Bernanke in 2002 at a conference honoring Milton Friedman's 90th birthday. Bernanke, who was a Fed Governor at the time, said: "we did it [The Fed made a mistake]." And went on to add: "thanks to you [Friedman and Schwartz], we [the Fed] won't do it [make the same mistake] again." [3]

This is an example of how important the interaction of research and policy is. It is also an example that highlights the difficulty in understanding what happened. Sometimes it takes a long, long, long time for something to become accepted. This is how research is done.

Wakatabe Great. We have to be aware that we first have made mistakes, and then we should learn from them. I am encouraged by Carl's reference to the historical narrative of macroeconomics and then by Athanasios's reference to how the theory has been filtered through the historical process by taking the example of the Great Depression. Indeed, central banks can and should learn from history, especially the history of economic and financial crises.

<Next page: Translation is one of the most important roles of central bank economists>

Translation is one of the most important roles of central bank economists

Wakatabe Next, I would like to ask you about how research at central banks should look like. In other words, how research at central banks can best contribute to promote the banks' mandates, the design of monetary and financial policy?

Professor

MIT Sloan School of Management

Orphanides From time to time, we have fads in academia that are sometimes based on pure academic research motives. They are very important but basic research is not always ready to be applied before it is properly filtered. The rational expectations revolution [of Robert Lucas] mentioned by Carl is a very good example of this.

This revolution took a couple of decades to be filtered slowly into policymaking. It's important for central banks to have research staff so that they can distill what is most important from academic research and translate it to what can be used for policy purposes.

But at the same time, the policymakers must be very careful not to fall into the trap of fads and be overly influenced by academics where the theories and the understanding are not tested.

Walsh Let me emphasize what Athanasios has just said, that is, a critical role of economists within central banks is translating academic research and presenting it to policymakers.

More particularly, their essential role is distilling what is useful from academic research and that is likely to offer real insights into policy questions. That's really an important role.

If it's lacking, then the policymakers within the central bank are not getting all the potential insights academic research can provide. This is true even for policymakers who have strong academic records and experience themselves, because it's tough to keep up on everything if you are a busy policymaker. So, you still need staff economists to look at what are the emerging trends in academia and to highlight those that really offer insights that policymakers need to think about.

Wakatabe I also think that translation or acting as intermediary between the academic community and the policymaking side is an extremely important role of central bank economists. So, I'm glad that we can agree upon this.

Orphanides True, but let me add one more thing. I used to work as an economist at the Fed and eventually moved to the academia. In my experience, watching things from inside and outside central banks is very useful.

From my past experience, very often the gaps in theoretical models become apparent first inside policy institutions and only later with a lag outside. So, researchers inside the central bank, if they are given sufficient time for research activity to develop those ideas, have an advantage in being at the forefront of policy research.

Actually, I myself had the luxury of it at the Fed. One of the most cited papers I have on monetary policy is about the Taylor rule.[4]

The idea of this paper was born during an internal briefing at the Fed. At the time, people in academic circles thought that Fed policy could be explained with the Taylor rule. Instead, using data actually available when policy decisions were made, I was showing that the Taylor rule was not really useful for explaining policy. Top Fed officials were very interested in these findings, which prompted additional research. Eventually it became a paper.[5]

This may be a good example of the importance of interaction between academics and central bank research community as well as how central bank economists can best contribute to policymaking and research.

<Next page: Academics and central bank economists have different incentives>

Academics and central bank economists have different incentives

Wakatabe That is very intriguing, thank you. So, we agree that we do need central bank economists who are aware of the fads and the pitfalls of new academic research.

Deputy Governor

Bank of Japan

My next question is what would be the key considerations to foster good central bank economists who have a balanced understanding of new developments in academic research and their limitations? And also how should the interaction between central banks and the academic community look like for better policymaking?

Orphanides I would like to first point out that policymakers need to be cognizant that the incentives in academia and elsewhere are very different. Researchers at a university want to do research that will be valued by their peers and be published in academic journals. And this kind of research will not necessarily be practical for policy purposes.

On the other hand, it's not right to adopt the same quantitative criteria of publication in the academia for researchers inside policy institutions.

In my view, the most valuable research inside the policy institution is the one that has an impact on policy, and a lot of that research in a good policy institution is only known inside the institution.

Another big difference is the degree of simplification of a model. When researchers in academia focus on a new idea, they are trained to simplify the models they use. In the process of simplification, the academics may throw out elements that are absolutely essential for policy analysis inside the central bank.

Walsh Following up on that, it's true that academics tend to simplify away things except the core issue one wants to address to really get strong insights and implications on that particular issue.

Given this, it's very important to have somebody who can say to the policymakers, "Yes, there is this literature and that result. But to get that, these are the important assumptions they make," because those assumptions don't usually hold in practice.

Speaking of the incentives for academics, it's hard to publish an article on, let's say, the optimal monetary response to some event that nobody thinks is ever going to happen. For people to be interested in your research, you need to pick topics that people are interested in. And so it's going to be inevitable that the research community is not going to focus on what turns out to be the new event that surprises everyone.

For example, academics would not pick up unexpected issues such as the global financial crisis, COVID-19, or recent surge of inflation, which caught policymakers by surprise as well.

If you think about the period leading up to the global financial crisis, the standard academic models had essentially no financial sector. There were a few exceptions, but not many.

( Link to the transcript ).

We had foundational work by people like George Akerlof who won the Nobel Prize on asymmetric information and how it can lead to fragility, particularly in financial markets. And in 2022, Ben Bernanke, Doug Diamond and Phil Dybvig won it for their work on financial frictions. [6] This work had important impacts on financial regulatory policy, but not as much on monetary policy until the global financial crises, because it hadn't really addressed what the consequences of these frictions for monetary policy might be.

Orphanides Yes, Carl's example is a good one for our point. The standard macroeconomic models before the global financial crisis were not very useful for understanding the crisis, because for simplicity, some features that proved important during the crisis had been eliminated.

So, economists inside the central bank needed to resurrect classical studies that take into account practical aspects relevant for the central bank, and integrate them with the new studies and methodologies to make them practicable.

In addition, in my opinion, it's very, very important for successful policy to integrate practice and theory from different fields.

For example, it's very important to have people who understand markets, because central banks operate in the markets. And it's very important to have both practitioners and academics to do this right.

Walsh Since the global financial crisis, we have seen the huge shift of resources within the academic and the central bank communities to start thinking much more deeply about financial frictions and their influence on the economy and financial markets.

These contributions are helpful for policymakers going forward in distilling which frictions create problems, and how we should address them through regulatory policy and monetary policy. I think this is another area where having that conversation between academic and central bank researchers is important.

Wakatabe Thank you very much for your fruitful discussions on the interactions between academic and policy communities. Occasionally, scholars make a distinction between "professional or disciplinary knowledge," knowledge by and for academics, and "practical knowledge," knowledge created and exercised by practitioners.[7] In central banking world, both are more closely related to each other.

<Continue to Series 2: "Art versus Science" in the Conduct of Monetary Policy (Coming Soon) >Notes

- Lucas Jr., Robert E. (1972) "Expectations and the Neutrality of Money," Journal of Economic Theory , 4(2), 103-124. [1]

- Friedman, Milton and Anna J. Schwartz (1963) A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, Princeton University Press. [2]

- Bernanke, Ben S. (2002) "On Milton Friedman's Ninetieth Birthday," Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke at the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [3]

- The Taylor rule is a monetary policy rule proposed by John B. Taylor. This rule expresses the short-term policy interest rate as a function of the inflation rate and the output gap. See Taylor, John B. (1993) "Discretion versus policy rules in practice," Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39, 195-214. [4]

- Orphanides, Athanasios (2001) "Monetary Policy Rules Based on Real-Time Data," American Economic Review, 91(4), 964-985. [5]

-

For more information about Akerlof's contributions to the study of asymmetric information and Bernanke, Diamond and Dybvig's contributions to the study of financial frictions, see the respective outreach information of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001 and 2022.

Nobel Price Outreach AB (2001) "Popular information: Information for the public," available at https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2001/popular-information/

Nobel Price Outreach AB (2022) "Popular information: The laureates explained the central role of banks in financial crises," available at https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2022/popular-information/ [6] - Furner, Mary O. and Barry Supple (eds.) (1990) The State and Economic Knowledge: The American and British Experiences, Cambridge University Press, 11-26. [7]

Carl E. Walsh is a Distinguished Professor of Economics Emeritus, University of California, Santa Cruz. Before joining the University of California, Santa Cruz, he served as a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. His fields of research are monetary economics and central banking. He is the author of Monetary Theory and Policy (Fourth edition, MIT Press, 2017). He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from University of California, Berkeley. He served as an Honorary Adviser to the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan between 2019 and 2022.

Athanasios Orphanides is a Professor of the Practice of Global Economics and Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management. From 2007 to 2012, he served as Governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus and was a member of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank. Following the creation of the European Systemic Risk Board in 2010, he was elected a member of its first Steering Committee. Earlier, he served as Senior Advisor at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, where he had started his professional career as an economist. His research interests are on central banking, finance, and political economy and he has published extensively on these topics. He holds undergraduate degrees in mathematics and economics as well as a Ph.D. in economics from MIT. He has been serving as an Honorary Adviser to the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan since 2018.

Masazumi Wakatabe is a Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan. Prior to joining the Bank of Japan, he was a Professor of Economics at the Faculty of Political Science and Economics at Waseda University from April 2005, and also a visiting scholar at the Center on Japanese Economy and Business of Columbia Business School from March 2017 to February 2018. He wrote extensively on economic crises such as the Great Depression, and his books include Japan's Great Stagnation and Abenomics, published in 2015. He holds a B.A. in Economics from Waseda University, and a M.A. in Economics both from Waseda University and from the University of Toronto.

- This trialogue was held in the mid November, 2022. The titles and information in this newsletter are as of the time of the trialogue.

- The views and opinions expressed in these newsletters are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the organizations to which they are or used to be affiliated.

- " Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve Board Building.jpg ” (the picture of the headquarter of the Federal Reserve on page 2) by AgnosticPreachersKid is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 .